Introduction

1During the 1890s, Theodor Lipps published and republished eight books and articles dedicated to the topic of optical illusions (Lipps 1891, 1892a, 1892b, 1896, 1897, 1898, 1900, 1905). These eight pieces should be read together: the later publications were explicitly written to pursue the argument made in the first, Ästhetische Faktoren der Raumanschauung (1891), and to make up for its argumentative inadequacies, in part by providing more experimental examples. The fundamental claim common to these publications is that aesthetic impressions and optical illusions (or optical impressions, as they are also referred to) are two sides of the same coin: “the optical and aesthetic impression we acquire of geometric forms are merely two sides of one and the same thing” (Lipps 1897, v).1 The claim is a strange one. It intentionally casts the relationship between an aesthetic and an optical illusion in an ambiguous light, since being two sides of the same thing implies both the identity and the difference of the phenomena in question. One is furthermore led to ask what type of interface or common ground these two phenomena might share and in what way they are derived from that common ground. Lipps’s initial answer that they share a root in the “representation of mechanical ‘activities’” does little to help clarify matters (Lipps 1897, v). It is far from obvious why optical illusions and aesthetic impressions should be regarded as standing in any type of relationship to one another, whether it be one of identity, reflection, or difference, and what relationship either might have to mechanical activities. Optical illusions, one would think, are a subject for optics or epistemology; the second type of phenomena are a matter of aesthetics; mechanical activity a concern for physics. Even when one considers the broad scope of the discipline of philosophy at the end of the nineteenth century as encompassing both psychology and aesthetics, it is an open question why optical illusions and aesthetic impressions should be treated jointly.

2For all its strangeness, the claim is by no means a historical anomaly. One might recall Gottfried Ephraim Lessing’s Laokoon oder über die Grenzen der Mahlerey und Poesie (1766), which argues that every artwork consists in an illusory presentation of a reality that is actually absent; an artwork achieves such an illusion by means of its use of signs, which ideally render this illusory reality present but at the same time make themselves transparent, that is, avoid being perceived. Looking forward, one thinks of Ernst Gombrich’s Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (1960), whose title suggests that it belongs to the disciplinary lineage of psychological aesthetics, which Lipps is in part to thank for founding. Described too simply, Gombrich interprets the history of art as the attempt to approximate reality through a process of perception and correction. That approximation is an illusory effect. Lessing and Gombrich thereby both advance an argument that has become familiar and intuitive to us, namely, that an artwork consists in an illusion since it feigns the presence of an object actually absent.

3Lipps’s claim, however, is of a very different kind. He does not describe an artwork as an illusion. In fact, his philosophical aesthetics has little interest for the properties of artworks or their reception. Thus, although it might appear helpful to contextualize Lipps in the history of aesthetics and art history I just sketched, his interest in illusions actually stems from a widespread fascination with optics and optical illusions in the late nineteenth century. Lipps is much more interested in the epistemological and psychological questions posed by optical illusions than in something specific to artworks.

4At first sight, the breadth of Lipps’s interest and his concern with fundamental questions in epistemology amplifies the difficulty of answering the question of how optical illusions and aesthetic impressions relate to one another. There appears to be no set of objects that would give rise to both optical illusions and aesthetic impressions. In the following, I attempt to make sense of the strange claim that optical illusions and aesthetic impressions are two sides of the same coin. Making sense of this claim helps us understand basic aspects of Lipps’s thought on perception and epistemology as well as the difficulties he has in defining the subject matter of aesthetics—although, curiously enough, aesthetics continues to be the discipline in which he is best remembered today. I will begin with Lipps’s account of perception in these texts from the 1890s, then turn to how he explains the mechanics of optical illusions and consider his methodology, and finally I will address the problem of aesthetics.

Lipps on perception

5Lipps’s claim that optical illusions and aesthetic perceptions are two sides of the same thing appears in the preface to the important work Raumästhetik und geometrisch-optische Täuschungen (1897), which I will focus on here. The book is introduced as a retort to criticisms lanced at Ästhetische Faktoren der Raumanschauung. In the preface, Lipps writes:

When I first approached the questions treated in this book, it was due to an external occasion. I had been asked to participate in the psychological Festschrift that was intended to be given to Hermann von Helmholtz on his seventieth birthday. I believed I could fulfill this request by further elaborating a thought that occasionally occupied me at the time and that seemed somewhat psychologically and aesthetically productive to me. But when I followed this thought through to its consequences and judged them against the facts, I saw that the same thought took on different faces and finally turned into a completely different thought. This new thought was, broadly stated, the thought that the optical and aesthetic impression we acquire of geometric forms are merely two sides of one and the same thing and have a common root in representations of mechanical “activities.” With that came the further thought that it must be possible to describe these mechanical “activities” in more detail and from there to derive geometric-optical illusions in a systematic way. I began to carry out this thought in my contribution to that Helmholtz Festschrift with the title “Ästhetische Faktoren der Raumanschauung.” The result was so rough, so correct, and so inadequate as the time I had available then allowed. (Lipps 1897, v)

6The passage gives a taste of Lipps’s prolix and often convoluted writing style—a serious impediment to modern readership. One is inevitably led to wonder how the metamorphosis and reversals of Lipps’s original idea relate to the metaphor of being two sides of the same thing. The passage also contains several important clues to Lipps’s account of optical illusions, the first of which is his repeated reference to the publishing context of the earlier piece. As Lipps repeatedly notes, Ästhetische Faktoren der Raumanschauung (1891) first appeared in a birthday Festschrift for Hermann von Helmholtz, the most successful and popular scientist in the nineteenth-century German-speaking world. Lipps is keen to position himself in a lineage with Helmholtz, both by publishing in the honorary work from 1891 and by invoking his name again six years later. Lipps hopes that these books and his philosophical endeavors at large will be understood as a continuation of Helmholtz’s scientific project. Most broadly, Lipps and Helmholtz see themselves as providing the scientific and experimental counterpart to Immanuel Kant’s transcendental philosophy by attempting to describe the empirical acquisition of the subjective form of the intuition of space. The argument that the mental mechanisms responsible for our intuition of space are natural phenomena and can be studied empirically goes back to David Hume, whose Treatise on Human Nature Lipps helped translate into German (Hume 1895). Helmholtz, Lipps, and their contemporaries thus belong to a historical moment in which the empirical and experimental methods of the natural sciences are tasked with answering fundamental questions in epistemology, such as:2 What can we know about objects in the external world? And why do these objects appear to us as given in space, time, and causal relationships? The empirical and experimental attempt to answer these epistemological questions is very much indebted to the configuration of the scientific disciplines in the late nineteenth century. Philosophy of the mind was yet to be differentiated from empirical psychology, art history from philosophical aesthetics, and philosophical aesthetics from the philosophy of the mind. When Lipps places himself in a lineage with Helmholtz in the introductions to his volumes from 1891 and 1897, he is situating himself within this fluid constellation of disciplines and methods, and attempting to forestall their specialized differentiation.

7Lipps more specifically intends to defend Helmholtz’s pursuit of a primarily psychological (rather than physiological or materialist) account of the mental representation of space: he believes that spatial representations can only be traced back to psychological mechanisms and not to biological structures.3 In the preface from 1891, Lipps aligns himself with Helmholtz against Wilhelm Wundt and Hugo Münsterberg, who had argued that spatial perception and optical illusions derive from and are in proportion to the efforts of eye movements. For Helmholtz and Lipps, in contrast, the perception of space is a product of a judgment based on past experiences. Helmholtz’s empiricism posits that our capacity for spatial representations is neither inborn, nor does the intuition of space belong to original perceptions. A mental representation of space is the result of applying, in judgment, an interpretative schema derived from the sum of past experiences to perceptual data.

8In his renowned Handbuch der physiologischen Optik (1867), Helmholtz defines the transition from perceptions to representation as a process of “inductive conclusions” or also analogies that assume the form of a syllogism consisting of a major premise (a rule: to use Helmholtz’s example, “All men are mortal”), a minor premise (the specific case: “Cajus is a man”), and a conclusion (“Cajus is mortal”) (Hemzholz 1867, 447). The major premise is, according to Helmholtz, itself an empirically verified inference. In this case, I have observed throughout my life that men do not live past a certain age, which leads me to conclude that men are mortal. I form that premise and make use of it in my conclusion “Cajus is mortal” without having to reflect on these past observations or having to carry through the syllogism consciously. The inductive process that constitutes the transition from perception to representation is logical, empirically grounded, and unconscious. Our inferences about the existence, spatial arrangement, and properties of objects rely on analogous premises and procedures, albeit ones that are much harder to describe. The conclusion that an object is present to my right on the basis of how light falls on my retina, for example, is based on a rule that must be learned and repeatedly tested for its validity (tests I perform though movements and actions that verify the efficacy of my judgments; a judgment is correct insofar as it permits me to perform an intentional action). As Helmholtz concludes, “Only when we, according to our will, bring our sensory organs in different relations to the object do we learn to judge with certainty about the sources of our sensory impressions, and such experimentation occurs from the earliest youth without interruption through the entirety of one’s life” (Helmholtz 1867, 452).

9For Lipps, as for Helmholtz, representations are “interpretations” or “judgments” that are secondary to perception but nonetheless unreflected, unconscious, and immediate. He adopts Helmholtz’s theory of induction with the crucial specification that our judgments of spatial forms are “mechanical” in nature. As Lipps very briefly suggests in the longer passage cited at the beginning of this section and will then spell out at great length over the course of the book, the transition from perceptual data to a representation is determined according to rules established in the perceiver’s kinesthetic experience. Optical illusions and aesthetic impressions have their common ground in how our past motions and movements are applied as schema to raw perceptual data.

10What are these mechanical activities and how do they provide the schema through which we make sense of and act in the world? Lipps, again like Helmholtz, remains committed to a mechanical paradigm that interprets the world as mechanical transactions of force.4 Each activity is mechanical in the sense that it constitutes an expenditure of force that prompts a reactive force: when I lift an object, it is activated into resisting my lifting, or when I stand up, the gravitational pull of the ground impedes my standing. The schemata that we employ in our representations of spatial forms are acquired in the sum total of quotidian motions, our experience of force and counterforce in a world of things. These rules are thus not only unconscious but also embodied. They can be acquired only because we are bodies in a world of bodies subject to the same mechanical conditions. Spatial forms are, in essence, interpreted in analogy to our own body, the source of our schematic rules.

The mechanical events outside of us are not the only events in the world. There are events that lie closer to us in every sense of the word, namely, the events in us; and these events in us are comparable or analogous to those events. But we have the tendency to grasp things that are comparable from the same point of view. And this point of view is always primarily determined by what is close to us. We thus observe the events outside of us in analogy to the events upon or in us or in analogy to our personal experience. (Lipps 1897, 5)

11The rules that allow us to make sense of objects in analogy to our own bodies are most importantly acquired in the ceaseless task of maintaining and risking our corporeal equilibrium. Maintaining our balance in the face of gravity’s pull gives us an unconscious “feeling” for what varied operations of force look and feel like. Describing how we acquire these interpretative schemata, Lipps points to the body in motion, with special emphasis on forms of motion that entail a precarious relation to the ground.

We walk, for instance, or run, practice the art of ice-skating or of bicycling, and at the same keep ourselves in secure balance. We do this even though the conditions of equilibrium constantly change, every unevenness of the ground, every breath of wind, every new position of the body or of one of its parts shifts it. What lies at the bottom of this are experiences. […] But in the moment when we are practicing the acquired art, we do not recall past experiences to adjust ourselves in every single moment to the experience that then particularly comes into question. […] We do not follow single experiences but rather the law or the rule that these experiences contain within them, especially the law or rule of equilibrium. (Lipps 1897, 36-37)

12In other words, past experiences have endowed us with the immediate ability (i.e. not requiring thought or premeditation) to predict and respond to impacts of force such that we continue to maintain our equilibrium. An (again unconscious) analogy between my body and other bodies allows me to apply these rules in judgments of external phenomena.5 Each event of the everyday in which we do not fall confirms the presence of this unconscious rule, a practical form of knowledge of equal significance to the content of consciousness or the interests of the will.

13Lipps clearly echoes Helmholtz when he emphasizes the unconscious nature of these rules derived from past memories: “Everyday life shows that mechanical experiences can guide us in our practical behavior and in our judgment without our having a conscious memory of the content of these experiences. Past mechanical experiences thus undoubtedly operate in us unconsciously” (Lipps 1897, 35). The claim also puts Lipps in an untenable philosophical position since he both wants to maintain that the representation of an object is both mediated by past experiences and also immediate (insofar as the analogy never has to be consciously reflected). Representations of space are thus supposed to retain crucial properties associated with perception – such as being in direct relation to objects – while they are at the same time essentially different from them. As remains to be seen, this conflict belongs to a greater epistemological problem that Lipps’s mechanical aesthetics faces.

Geometric-optical illusions

14What then do we perceive through the lens of “mechanical interpretation”? Although Lipps focuses almost entirely on geometric forms because they supposedly more clearly lay bare the relationship of force and the nature of optical illusions, he begins with the classical example of a column. We represent the column to ourselves by way of an unconscious mechanical interpretation. The representation arises according to the mechanical conditions that we judge as making this form mechanically possible.

In one word, we make the column an object of a mechanical interpretation. That we do this is not a matter of our will; it also does not require any reflection; the mechanical interpretation is, rather, immediately given with the perception of the column. What we perceive is immediately attached to a representation of how, based on thousands of experiences, such a form or spatial mode of being is possible or is able to endure. (Lipps 1897, 5)

15Because we rely on kinesthetic categories acquired in embodied life, what we see in the column is not a static form but activities of force or motions: the acts of pulling oneself together (literally, sucking in one’s midsection) and standing upright to overcome the threat of formlessness posed by the body’s weight. The perceiver knows both of these activities to be necessary to the preservation of form because of her own experiences standing up, column-like. What one sees on the basis of this mechanical interpretation is a form striving upward and pulling itself inward to resist the strain of gravity and a possible dissolution in entropic formlessness. One’s experiences then appear to be in the form—Lipps struggles to find the right preposition. Although Lipps does not yet speak of empathy (Einfühlung), it is clear that the application of bodily experiences and feelings onto the form of the column—which gives rise here to a “feeling of sympathy” (Sympathiegefühl)—lays the groundwork for a later theory of empathy.

Before my eyes, the column seems to pull itself together and to stand upright, that is, to behave similarly to how I behave when I pull myself together and stand upright, or when in defiance of the gravity and natural inertia of my body, I remain pulled together and upright. I cannot perceive the column at all without seeing this activity as lying immediately contained in what I perceive. […] I sympathize with the Doric column’s way of behaving or of activating an inner liveliness, because I recognize in it a natural way of behaving that is my own and delights me. All joy about spatial forms and, we can add, all aesthetic joy in general are thus an exhilarating feeling of sympathy. (Lipps 1897, 7)

16What we accordingly see in the column is a form that reflects the shape and activity of the human body as well as the conditions of its well-being; I feel pleasure in the sight of the column because it appears as a body at ease, one that does not struggle to maintain its uprightness because its upward force is more than sufficient to constitute its form. Lipps’s theory of optical illusions thereby unexpectedly seems to return to architectural treatises of Vitruvius, who derives the rules for architectural beauty from their analogy to the human body.

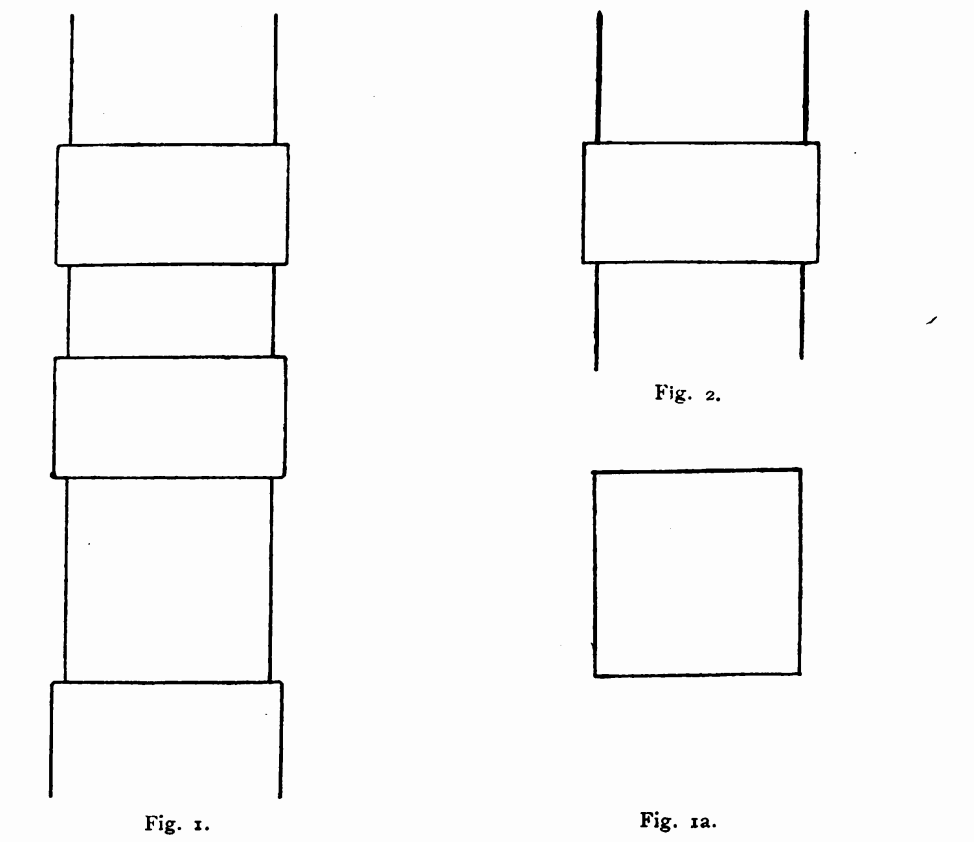

17In Ästhetische Faktoren der Raumanschauung (1891), Lipps demonstrates the two basic activities that determine the form of a column and the ensuing illusion pictured in the diagram in figure 1. The upward-driving force seems so powerful that a column appears much taller and skinnier than it actually is (the top half appears extended compared to the bottom half), and it may even seem to hover slightly above the ground in an act of levitation. The illusory nature of my perception thus consists both in seeing motion or activity where there is none and in seeing a shape different from the one given: my representation of form has different geometric properties than the form actually present. Optical illusions occur when we interpret a form as the activity of forces, apply related associations, and exaggerate specific kinetic tendencies. “Optical illusions take place when we carry out the tendencies or activities that seem to lie immediately in spatial forms” (Lipps 1896, 43). In the depicted diagram, we are meant to judge the square imbedded in the vertical form on the left (figure 1) as being taller than the stand-alone square on the right (figure 1a, though notably, Lipps never explicitly states as much, writing only that the “exaggeration is such a striking one”) (Lipps 1891, 7). The illusion supposedly results because, having picked out the force directed upward as the dominant feature of the form on the left—the one we are most inclined to identify with on the basis of our corporeal experience (as upright beings)—we exaggerate the effect of that force in our mental representation.

18The assumption underlying Lipps’s description of human behavior, that we are always striving to avoid formlessness, is operative here as well. The investment in the persistence of forms is reflected in the assertion that we exaggerate those tendencies in our mental representations that must be strongest for forms to endure: “Spatial or mechanical forces thus appear to operate in spatial forms. The function of these forces is not altering the form but retaining it, that is, resisting or opposing a change that would take place if the forces were not there or remained inoperative” (Lipps 1896, 40). For that reason, many of the illusions Lipps analyzes abide by a normative preference that a force always be matched by an equal and opposing counterforce. A letter imbedded in a circle, for example, when contrasted with an unbound letter, appears larger, because we imagine the lines of the letter as compelled to exert a force equal to the pressure of the enclosing circle

19Central to Lipps’s account of optical illusions is the claim that they do not constitute exceptions to human visual experience: “optional illusions are, after all, not exceptions but take place everywhere.” As a result, “we never see what is; and never see what we believe we are seeing” (Lipps 1892b, 504). In fact, their ubiquity serves as further evidence for the centrality of mechanical schemata to sense-making. As Lipps writes at another point, it is “a habitual necessity to represent forms as narrowing or broadening,” just as for Helmholtz the reliance on past experiences or on analogies is an inevitable yet learned part of our representational faculties (Lipps 1896, 45). The claim that optical illusions pervade perceptual experiences reveals that Lipps’s interest in optical illusions is an attempt to answer fundamental epistemological questions as to what we can know about the external world. Rather than claim, like Kant, that we can never know the thing-in-itself because we always perceive the object through the categories of judgment, Lipps conceives of the difference between the thing-in-itself and our representation as a problem of optical illusions. The theory that we apply schemata derived from past corporeal experiences onto perceptual data so as to represent objects in space to ourselves is meant to explain the difference between intuitions and judgments, perceptions and representations, and to demonstrate how it is possible for us to have knowledge of the world.

20To claim, however, that our representations consist in optical illusions is of a very different nature than to say we cannot know the world without our categories of judgment, since the classification of an optical illusion as such presumes that we know the difference between the thing-in-itself and how we see it. Lipps’s epistemology, in other words, does not remain agnostic on the thing-in-itself. If I know that my perception of a square’s verticality is exaggerated, then I must be able to know—whether through reflection or quantitative experimental methods—that the square imbedded in the column is actually of the same height as the square to the right (figure 1). Indeed, Lipps’s diagrams rest on just that assumption: they allow us to measure the true heights of rectangles and to compare them with our illusionistic representation. An analysis of the illusionistic aspects of perception necessarily presumes that we can know the way things really are as compared to our distorted representations, that the illusion can always be interrupted. The diagrams that give rise to the illusions are meant, after all, to represent the way things are and, thus, to give us the means to identify and measure the degree of our illusory perception. Once again, Lipps’s epistemology is troubled by the conflictual claims I named earlier, that these representations are meant to be immediate (unreflected) and mediated (though the schemata of interpretation). If our representation of the object is immediate, then it should be impossible to experimentally test the degree of the illusion and its deviation from reality. For the sake of the coherence of his argument, Lipps should be compelled to claim that representations are mediated.

21Against the worry that Lipps places the perceiver in a hall of mirrors, in which he is perpetually suspended in a world of illusion, Lipps assures us that the distortions that occur are minimal. Optical illusions, which he at other points calls “modifications,” do not radically alter what we see (that would certainly compromise the objectivity of perception), meaning that they do not greatly estrange human subjects from the world. They largely consist in exaggerations of degree such that, for example, we perceive one line to be somewhat taller than a second line, even though, on the page, they are equal in length. Optical illusions, one might be led to conclude, are pervasive but insignificant—a conclusion that would, of course, call the significance of Lipps’s prolific output on the topic into question.

22Lipps further qualifies the significance he attributes to optical illusions when he writes that every form is capable of producing multiple illusions or no illusion at all. Since multiple forces are active in every form, and since each illusion is produced by the exaggeration of one force over the others, multiple optical illusions are always possible. “Each of these tendencies,” Lipps writes, “asserts a demand to be realized by us in representation. Every spatial form therefore possesses the possibility of opposing optical illusions” (Lipps 1896, 45). These possibilities “compete […] in our representation” (Lipps 1896, 56), their actualization being contingent on how the beholder describes the form or what aspects she attends to. If the viewer’s attention moves from one tendency to another, it is moreover possible that “the illusion on occasion turns into its exact opposite” (Lipps 1897, 201). In the case of the two rectangles in figure 1, for example, excessive reflection on the weight born by the column (which is, as remains to be shown, a departure from an aesthetic perspective) might lead the perceiver to exaggerate the downward draw, resulting in a representation shorter and squatter than the square actually given. The instability of these illusions naturally also calls into question the possibility of philosophical inquiry into them and their value for epistemology.

The illusions

23Many of Lipps’s geometric forms are variations on popular late nineteenth-century optical illusions that were circulating in German psychological and optical publications, including the the Müller-Lyer, the Delbœuf, the Ebbinghaus, and the Zöllner illusions.6 Partially as a result of what Lipps is willing to classify as an illusion, this analysis belongs to the most enigmatic part of his work. What he presents, over hundreds of pages, over many years, are examples of optical illusions that are often impossible to recognize as such. They are, as I noted, primarily illusions concerning size and kinetic activity. The fundamental argument is that these ubiquitous optical illusions occur according to systematic rules that can be deduced from these examples. The objective of Lipps’s extensive examination of optical illusions is to show the systematic way in which mental representations of form deviate from forms in the external world because of our sense-making procedures. Lipps purports to have deduced systematic rules through self-experimentation and the testing of further subjects. The reproduction of the figures in the book should allow the reader to reenact the author’s visual experiments, to see the illusion, and to be convinced by its evidence. The book thereby becomes an experimental tool with evidentiary value. To ensure that the illustrations fulfill this purpose, and because the examples were very often a point of dispute between Lipps and his critics, the beginning of Raumästhetik includes a user’s guide on how to perform these optical experiments.7

Concerning the manner of observing the figures, it must of course occur without preconceptions. When it is a matter of comparing different figures, one would do well to certainly retain the actual elements of comparison but otherwise to repeatedly move back and forth with the eyes between the figures as thoughtlessly as possible and not too slowly. (Lipps 1897, vi)

24Lipps further specifies that the examples described but not reproduced or ones specific to different media should be drawn and tested by the reader.8 These instructions, which demand that the reader identify elements of comparison, along with the abundance of examples, many of which constitute minute variations upon one another, suggest that the argument strongly relies on popular methods of comparative seeing.9

25Lipps nonetheless admits that even when these instructions for experimentation are followed exactly, it may be difficult to reproduce the illusions as he has seen them. He reports that even among his test subjects, the differences in the type of illusion and in the strength of its effect were highly variable. In this regard, “variations of subjective conceptions could play a role” (Lipps 1897, 201).10 The scientific attempt to deduce systematic rules for the perception of optical illusions is very much at odds with what was considered to be the embodied and subjective nature of vision.11 Lipps’s incredible but unlikely project is to insist that despite these subjective differences, it is possible to identify objective (and universally valid) rules that determine the genesis of our representations and their qualities as illusions.

Life-like forms

26As I have noted, the broad epistemological scope of Lipps’s projects makes it difficult to isolate aspects specifically related to aesthetics, much less to the reception of artworks. If optical illusions are ubiquitous, and aesthetic impressions are nothing but the flip side of these illusions, then it would seem that we perceive the world around us aesthetically without exception. His work is continually challenged to differentiate aesthetic experiences from our perception of forms generally. At the same time, his theory does encompass a normative dimension that loosely defines what conditions forms must satisfy in order to elicit the judgment “this is beautiful,” or a feeling of pleasure (Lust), the two criteria by which Lipps distinguishes an aesthetic experience. To name those conditions, mechanical aesthetics must explain the difference between “mechanical events,” where mechanical laws are merely descriptive of what happens, and events that “become aesthetic-mechanic,” in which these normative expectations are satisfied (Lipps 1897, 34). To reiterate the claim with which I began this essay: an optical illusion based on a mechanical interpretation is both the same as and different from an aesthetic impression of the same phenomenon or form. While a mechanical interpretation always precedes the judgment that a form is beautiful, not every form interpreted as the activity of force is beautiful. Ultimately the descriptive and normative threads of Lipps’s work are ultimately exceedingly difficult to disentangle.

27In effect, mechanical aesthetics makes three important prescriptions for beautiful forms. It first demands that the activity of force be made so powerfully present that the form appears lively. As unlikely as it seems, Lipps’s rudimentary geometric forms stand in the tradition of Pygmalion and rehearse the topos of an artwork’s liveliness (See Boehm 2003, 95). An artwork achieves an impression of liveliness by juxtaposing forces in a manner than intensifies their strength and compels us to apply mechanical schemata to our interpretation of the form: “It is the task of the arts of beautiful spatial form to intensify and multiply this reciprocal effect, to make present for us in forms a rhythm of liveliness that is meaningful and that consolidates it into a meaningful whole” (Lipps 1997, 79). The lessons drawn from the study of optical illusions are important in this respect because they explain how particular combinations of geometric forms contribute to the intensification, complexification, and unification of the impression of force. The analysis of optical illusions predicts the liveliness of different geometric forms. For example, the illusion concerning squares in figure 1 illustrates that imbedding a square in a taller composition provokes viewers to exaggerate the strength of the upward force. The taller the form, one might then conclude, the more likely that it is perceived with pleasure as lively, until, of course, an excess of height induces a state of vertigo in the perceiver.

28What’s more, the impact of force should be so strongly foregrounded that it permits viewers to overlook the form’s materiality. A beautiful form is one that manifests the pure activity of force. An aesthetic impression of the column arises, for example, “when we disregard the material,” because that material disguises and diminishes the pure presence of force. Only once an object has been stripped of its matter and abstracted into a diagram of pure force—as the geometric forms that Lipps employs supposedly do (overlooking, of course, the matter of paper and ink, and the weight of Lipps’s tomes themselves)—may we speak of an aesthetic form. “Standing upright is attached, as we saw, not to the material mass but to the vertical, straight gestalt” (Lipps 1897, 17). For that reason, the sketch of an upright rectangle can more effectively produce the aesthetic impression of a column for us than a column itself can. This produces a rather paradoxical account of aesthetic experience, since the impression of a form striving upward depends on the idea that it is subject to gravity, which, in turn, acts on matter. Lipps’s most prominent example of an aesthetic form has us imagine an immaterial column resisting being dragged to the ground.

29Ultimately, Lipps explains, all the spatial arts have found means of deflecting attention away from their materiality, such that the impressions of liveliness (Lebendigkeit) they deliver do not adhere to the formative material. “In these spatial arts [ceramics, tectonics, and architecture], what constitutes their actual object, the force-filled or lively space, still appears materialized, the role still has a material carrier” (Lipps 1897, 16). In contrast to such arts that seem to materialize lively space, ornamentation creates animated space without first having to overcome the burden of materiality. Because he deems material substance as a distraction that deflects attention away from the activity of force, geometric forms—pure diagrams of force—crown Lipps’s hierarchy of the arts.

If, however, only the force-filled or lively space is the object of the arts of the abstract configuration of space, then nothing stands in the way of the material carrier’s losing its role. […] So too can the spatial form appear for itself in the arts of the abstract configuration of space, not materialized, at least not materialized in the sense in which the marble column materializes its spatial form. We have thereby arrived at ornaments, as I might simply draw them with pen on paper. (Lipps 1897, 16-17)

30The celebration of ornament—and the claim that geometric forms are the most lively of all the arts—thus represents an interesting departure from the topos of liveliness in art, in which liveliness had been thought to depend on a visible resemblance to living things (Boehm 2003). The standard Lipps introduces maintains that beautiful forms need only resemble nature insofar as they manifest force. Aesthetics must demonstrate that artworks are made of the same interplay of forces that shapes the world, but they do not have to look like living entities. The figural dimension of aesthetic objects has been displaced from a surface resemblance to an analogy of structures, in which geometric forms are structured by relationships of force like those of our bodies.

31While Lipps’s mechanical aesthetics enthusiastically celebrates the art of ornamentation, it is the art of architecture, as the emphasis on gravity throughout Lipps’s descriptions suggests, that serves as the archetype for geometric forms and the arts in general. Ornament manifests the forces we know to be at work in architectural structures—gravity and the counterforce that constitute form—in their purity. Geometric forms, in other words, are abstract, immaterial renderings of tectonic structures: “This ornament is just as well an artwork of the abstract configuration of space as the most sublime building. It says something similar to us, through the same means of geometric form, only without the tangible mass” (Lipps 1898, 17). Mechanical aesthetics thus borrows its principles for what constitutes a well-built form capable of self-maintenance from architecture and shows how its forms can become beautiful by foregrounding the activity of force while also removing the material carrier.

The problem of aesthetics

32Sufficient energetic liveliness ensures that the formal whole strikes the viewer as being engaged in activities subordinated to the task of homeostasis like a living entity. To appear lively constitutes both the aesthetic impression of form and is also in itself an illusion. To appear lively entails—and this is the second crucial condition of a beautiful form—that it appear as a unified whole, like an organism in which the activity of each organ is subordinated to the task of homeostasis. The pleasurable impression of a form depends on the suggestion that it is engaged in life-sustaining activities, to which each element of the form contributes. A form that appears as such a unified whole is also one easily understood; it does not, in other words, challenge our interpretative schemata.12 In contrast, a form in which the relationships of force and counterforce are not immediately apparent can never be beautiful. Our representation of form must be unified, just as each individual activity of force is subordinated to the purpose of maintaining the whole.

33To be comprehensible also means that the form is more easily related to the motions and activities of life. Although Lipps does not want to deny that there are relationships of force that belong to aesthetic objects independently of our representations of them, an aesthetic impression depends on being relatable to our kinetic experience. It is that relationship that constitutes the ground for their liveliness and a unified conception of them. Beautiful forms, in other words, do not appear as foreign species of life; they appear to share the experiences particular to our human life. Lipps writes: “All such vivification of our ambient reality comes about and can only come about when we transfer what we experience in us, our feeling for force, our feeling of striving or willing, of activity or passivity, into the things outside of us and into what happens upon or with them” (Lipps 1897, 6). At different points, Lipps describes the same process as transferring the “content of this feeling of being alive [Lebensgefühl] into the forms. […] The mechanical events in them thereby first become aesthetic-mechanical events” (Lipps 1897, 34).

Conclusion

34This account of aesthetic experience reiterates once again the very problem with which I began this essay. If, as I hope to have shown, Lipps’s epistemology and description of optical illusions is borrowed from Helmholtz insofar as the mental representation of an object is always informed by rules established in past experiences, then it would seem that all knowledge of the external world could be described as transferring our Lebensgefühl into a perceived object. Lipps seems to say as much when he repeatedly equates aesthetic impressions and optical illusions, for example, when he writes: “The ‘fantasy that vivifies everything’ […] fills everything with our life. Geometric forms have this vivification to thank for their aesthetic value. […] Insofar as geometric-optical illusions are based on the same activity as this aesthetic fantasy, they can also be called aesthetic-optical illusions.” (Lipps 1896, 40). That equation both strips aesthetic experience and optical illusions of any specificity. Optical illusions are no longer acknowledged as a destabilizing factor that places in question our relationship to the world of things and the possibility of knowledge. They have been made innocuous and insignificant. Aesthetic experience too is no different from quotidian perception, in which we make sense of the world on the basis of past experiences.

35In later publications, Lipps increasingly abandons this identity of optical illusions and aesthetic impressions. Optical illusions and aesthetic impressions may share a root in the interpretation of forms according to past kinetic activities, an interpretation that makes the form appear as if in motion. Nonetheless, aesthetic experience could and should be distinguished from quotidian perception, as well as from pervasive optical illusions, on the basis of a third criterion of the judgment that a form is beautiful. The feature of aesthetic experience that Lipps offers as a third distinguishing characteristic of an aesthetic impression—and to which he should hold fast (given, once again, that aesthetic impressions are those that permit the perceiver a feeling of pleasure)—is that the aesthetic form should evoke pleasurable corporeal situations of ease, equilibrium, and grace. A form is beautiful if its behavior reflects the activity we associate with a purposeful life. An upright form like that of a column or a tall rectangle is thus especially conducive to an aesthetic impression because they remind us of our own purposefulness as upright, bipedal beings: “Despite all ‘mechanics,’ the forms remain forms of art because we transfer our I into them, so as to take this I back again into us not as we know it empirically but instead enriched, expanded, elevated, as an greater, better, purer I” (Lipps 1897, 423). Although this account of aesthetic experience is certainly zealously idealistic and thus deeply problematic, it succeeds in giving an account of the difference between an aesthetic impression and an optical illusion: while quotidian perception and optical illusions rely on the sum of empirical experience, aesthetic impressions select from those empirical experience according to normative expectations concerning corporeal well-being. The beautiful form is the form of an upright, purposeful life free from the contingencies of embodied life and the very contingencies that pervade optical illusions.

- 1 All translations from German are my own.

- 2 For a discussion of empirical methods in aesthetics within the context of the disciplinary landscape around 1900, see Wilke, Müller-Tamm & Schmidgen (2013).

- 3 Lipps allows that these psychological mechanisms and physiological structures are parallel phenomena, but argues that we cannot know the latter. As Tobias Wilke convincingly argues, metaphors of Einfühlung were coined with the specific purpose of bridging this gap. See Wilke (2013).

- 4 For a defense of such a mechanical paradigm, see Helmholtz (1995). For an extended discussion of Lipps’s account of embodied human experience as expenditures of force, also in the context of empathy aesthetics, see Maskarinec (2018, 59–77).

- 5 Lipps relies on the significance of the analogy for the nineteenth century, in particular for the sciences of mechanics. In a mechanical paradigm, if a mechanism is discovered in one science, it can, by virtue of the posited universality of mechanical laws, be applied to further domains. Mechanics thus provides Helmholtz and his followers with justification to draw explicit analogies between different systems of forces, to compare, for example, the human body, the steam engine, and an electromagnetic telegraph system, all of which, Helmholtz claims, function to convert the input of one kind of force (food, coal, electric impulse) into another kind (calories, heat, electric series) capable of performing work. See Helmholtz (1995).

- 6 Many of these examples and the general fascination with seeing motion as an optical illusion in the late nineteenth century are documented in Schuler (2016).

- 7 For an example of such a dispute, see Lipps’s article “Ästhetische Einfühlung,” where he responds to Konrad Lange’s criticism that “he has never found fulfillment in the form of a spiral,” explaining that, even if the spiral seems strange to him, he has certainly experienced the rhythm of “forces, inhibitions, resistances” and how they are defied by the spiral’s form. Lange has simply failed to relate his own experience of the same rhythm to the spiral’s form so as to endow it with a “personal coloring.” See Lipps, (1900, 438-440).

- 8 Following a request to the reader that she only judge the work on the basis of thorough attention to its entirety (no small request for a four-hundred-plus-page tome illustrated with hundreds of illusions), Lipps writes, “A second request concerns the accompanying figures. These are numerous and yet insufficient. I often selected only one figure or a few from a series that would have been necessary. In these cases, I cannot guarantee that the conditions for the theoretically postulated optical impression are favorable for the reader in the figures I selected. There the reader will thus have to draw himself and thereby vary the conditions.” See Lipps (1897, vi).

- 9 For a very broad overview of practices of comparative seeing in aesthetics, the arts, and the sciences and their rise to prominence in early twentieth-century art-historical methodologies, see Bader, Gaier & Wolf (2010).

- 10 To explain why, in some cases, the expected illusion does not occur, Lipps distinguishes between the (theoretical) “necessity of an illusion [Täuschungsnötigung]” one we should expect given our preferences, and a “factual illusion.” See Lipps (1898, 147). A systematic analysis of optical illusion should make it possible to describe illusions that a form might produce even if they do not ensue. This, of course, very much undermines the evidential weight of experimental results, since the laws of mechanical-optical illusions may take precedence over the actual data.

- 11 The project is unlikely not only because its objective to identify general rules of perception is at odds with the variability of its results but also because it goes against the strong nineteenth-century trend to perceive vision as strongly subjective and thus unreliable. See Crary (1999, 12).

- 12 “As already noted, the possibility of a unified conception, or the ‘comprehensibility’ of a geometric composition in this sense, a fundamental condition of an aesthetic impression” (Lipps 1896, 43).